Gelatin plate monoprinting is a form of printmaking that utilizes a gelatin plate as the printing surface, as opposed to a carved block. The basics of printing are that we apply paint/ink to an object, and then print that onto another surface like paper or wood.

With a more traditional carved stamp of linoleum, wood, or even a potato, we can print many copies of the same design easily. This is called block printing. The print grabs most of the paint, and we apply more paint for the next print.

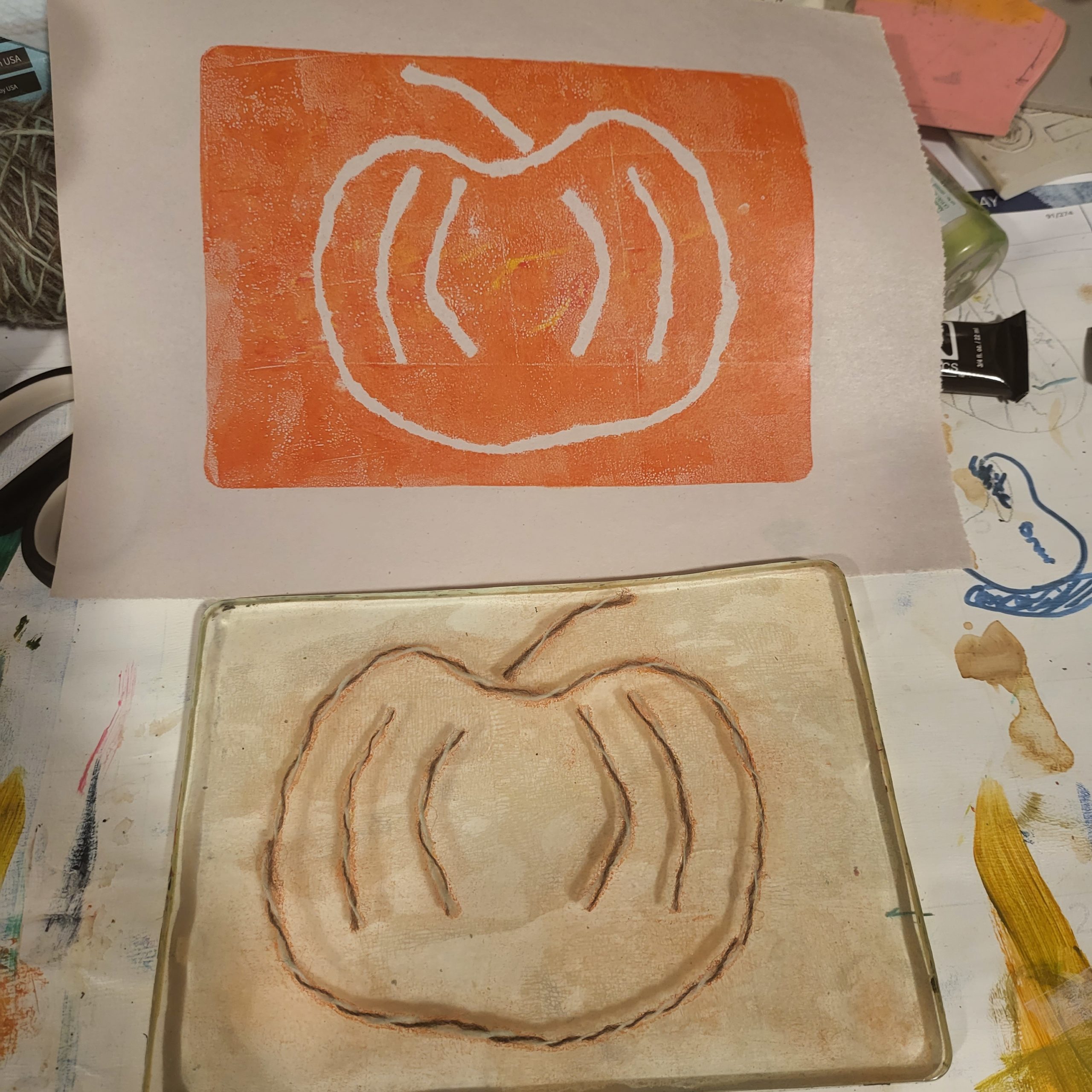

In gelatin plate monoprinting, we start by creating a design on the gelatin plate using various tools and techniques. Once the design is complete, the plate is inked and pressed against paper to create the final print – just as with regular printing (or silk screening). The paper grabs most of the paint, and we have an empty gelatin plate again.

Hence the term “monoprinting” – making one print. This is a detriment if we have a design you love that you want to print over and over; it’s a benefit if we haven’t figured out that perfect design. With block printing, we carve the design ahead of time – there’s an upfront cost.

The beauty of monoprinting is that the plate can be reused and modified again and again, allowing for endless experimentation and iteration.

This process is similar to how product management experiments are done, where different strategies are tested to find the best solution. Before we “carve a block” – create the product, whether it’s a software product, a physical product, or even testing a strategy – we want to experiment with different elements to see what’s going to be optimal.

One key aspect of both gelatin plate monoprinting and product management experiments is the concept of iteration. In printmaking, the artist can continue to make adjustments and modifications to the plate, testing out different techniques and tools to see what works best. In product management, experimentation allows product managers to try out different ideas and strategies, gathering data and feedback to inform future decisions.

We want to be able to set up and complete experiments quickly, and in a way that teaches us something. Often, product management (and art!) experiments do not dig deep enough into failures and successes. Are we learning more than “that didn’t work”?

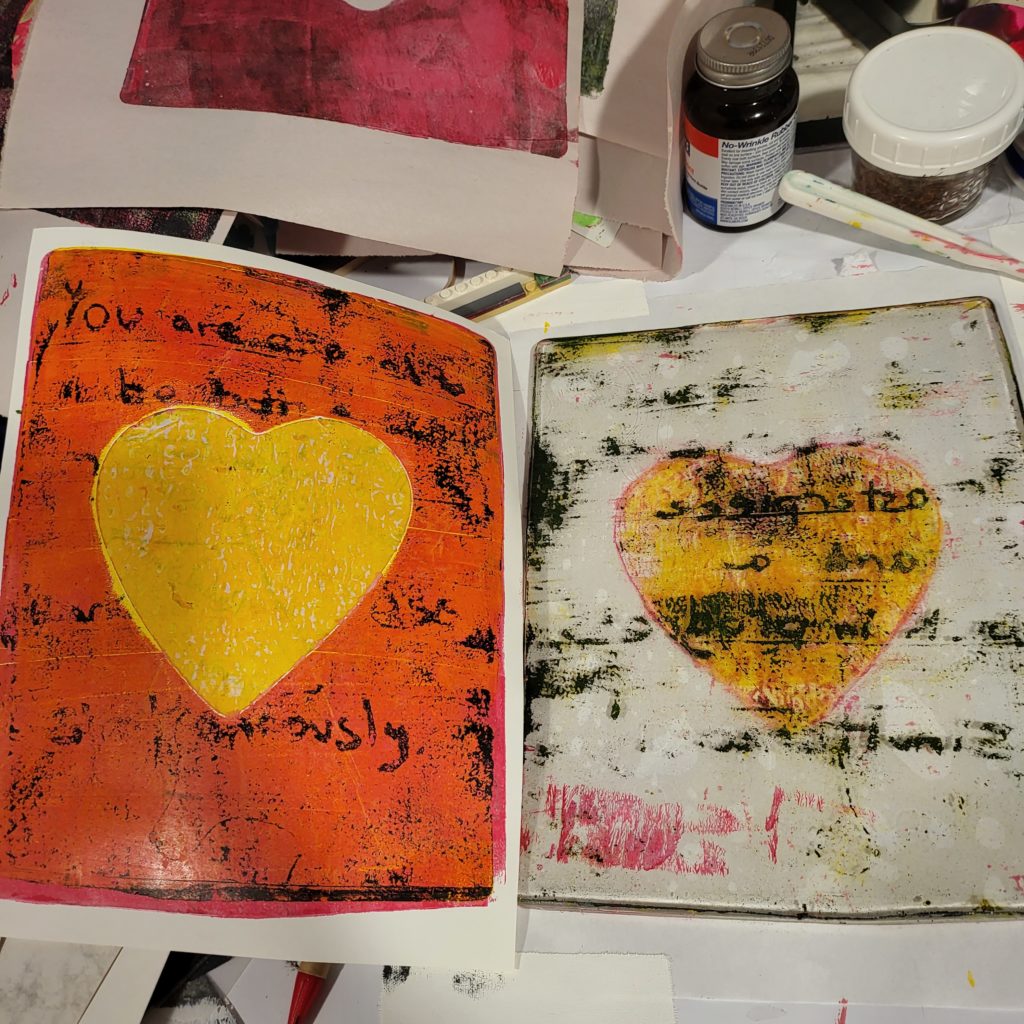

With gelatin printing, I’ve learned a lot the hard way, especially when layering prints. I need to understand more than just “when I put that blue on top of that purple, it disappeared.” I need to understand if it’s possible to EVER put blue on top of purple – it is possible! – and if so, how to do it – use an opaque blue. I can buy a more opaque blue; I can go a step farther and learn how to make the blue I have more opaque.

Similarly, we need to understand more about why our product experiments succeed or fail. Often our experiments succeed in testing but fail in the ‘real world’, and we don’t dig deep into the factors of success before declaring victory and proceeding to develop the product.

Another critical similarity is the element of surprise. Gelatin plate monoprinting is known for its unpredictable results, as even small changes in the plate can have a big impact on the final print. In product management, experimentation can also lead to unexpected and valuable insights. For example, a product manager may discover a new use case or customer segment we did not consider before.

It’s important to note that experimentation doesn’t necessarily mean that the final product will be perfect, as in product management it’s not always possible to have the perfect solution. Both in gelatin plate monoprinting and product management, the process of experimentation and iteration allows for continuous improvement and learning.

The unpredictable and creative process of gelatin plate monoprinting can serve as inspiration for product managers to think outside the box and approach problem-solving in a unique way. Both techniques allow for continuous learning, improvement and adaptability, leading to the best possible outcome.

I have also found that failing fast in art helps me be more comfortable with running experiments with an unknown outcome – if this idea fails, I can try another one. And in the end, most of the time, I make the biggest mistakes first – so I can get those out of the way in the experiments.